In his novel Zone 23 (SS&C Press, 483 pages) expat playwright C.J. Hopkins depicts a society, much like ours at its worse — some six or seven hundred years in the future — when any departures from prescribed ways of thinking are pathologized. Being melancholy, pondering larger philosophical questions, or contemplating the lack of fairness of the system can earn one a diagnosis of mental illness. Virtually everyone is on medication. Those who can’t be controlled by medication are deemed “Anti-Social Persons” and are removed from the society of “Normals” and relegated to various zones of abandoned and bombed-out cities, where they are eventually blown to bits by gamer-controlled drones.

In his novel Zone 23 (SS&C Press, 483 pages) expat playwright C.J. Hopkins depicts a society, much like ours at its worse — some six or seven hundred years in the future — when any departures from prescribed ways of thinking are pathologized. Being melancholy, pondering larger philosophical questions, or contemplating the lack of fairness of the system can earn one a diagnosis of mental illness. Virtually everyone is on medication. Those who can’t be controlled by medication are deemed “Anti-Social Persons” and are removed from the society of “Normals” and relegated to various zones of abandoned and bombed-out cities, where they are eventually blown to bits by gamer-controlled drones.

Human reproduction is the central theme. That, too, has been pathologized. Continue reading

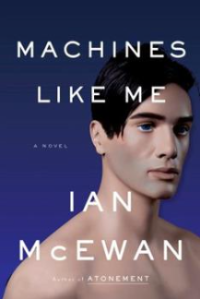

Machines Like Me (Nan A. Talese, 352 pages) by Ian McEwan is set in the possible world of the 1980s if Alan Turing had not died in 1954, Kennedy had not been shot in Dallas, and Britain had not won the war in the Falklands. In the story, Open Source information has allowed technological progress to sprint ahead, and the automatization of work is leading, first to high unemployment and then, presumably, to the creation of a universally idle population supported by the labor of machines. The hero, Charlie Friend, has recently purchased a life-like robot named Adam and he and his new love interest Miranda Blacke will together train and condition Adam to develop a personality and consciousness.

Machines Like Me (Nan A. Talese, 352 pages) by Ian McEwan is set in the possible world of the 1980s if Alan Turing had not died in 1954, Kennedy had not been shot in Dallas, and Britain had not won the war in the Falklands. In the story, Open Source information has allowed technological progress to sprint ahead, and the automatization of work is leading, first to high unemployment and then, presumably, to the creation of a universally idle population supported by the labor of machines. The hero, Charlie Friend, has recently purchased a life-like robot named Adam and he and his new love interest Miranda Blacke will together train and condition Adam to develop a personality and consciousness.